Trees of Life

When it comes to wildlife, trees can be worth more dead than alive.

Guest post by arborist Brian French

As a community, we have the ability to support wildlife throughout our region. Landowners, in particular, hold a unique opportunity to steward local flora and fauna. By changing how we manage trees in our landscape, we can help tend to the needs of an array of wildlife known as cavity dwellers.

As a community, we have the ability to support wildlife throughout our region. Landowners, in particular, hold a unique opportunity to steward local flora and fauna. By changing how we manage trees in our landscape, we can help tend to the needs of an array of wildlife known as cavity dwellers.

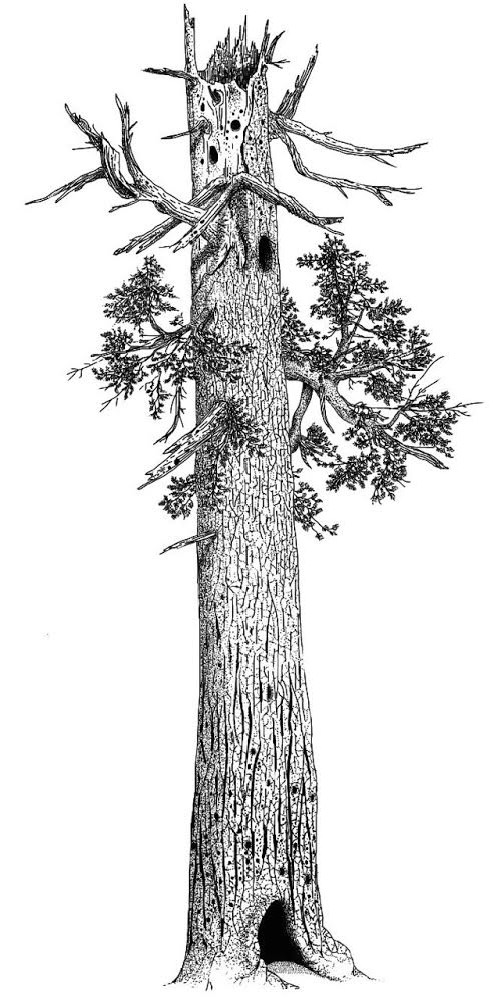

Pileated woodpecker, great horned owl, kestrel, chickadee, clouded salamander, flying squirrel, and many other species depend on cavities found only in dead trees. For many of these animals, life begins during a tree’s dying cycle. With this in mind, we should consider the value of deadwood and dead trees as habitat.

The presence of dead or dying trees correlates with the populations of wildlife that depend on them. In fact, species that rely on deadwood act as bioindicators of a forest’s health. One example, the acorn woodpecker, thrives in oak savannas by storing acorns in a mosaic of caches within the surface of deadwood. And little brown bats roost in small spaces behind the peeling bark of trees that have recently died. Far more wildlife live in dead trees than in living trees since hollows and cavities offer a place for thermal regulation, protection, foraging, food caching, and raising young.

As an arborist, I make many decisions with wildlife habitat in mind. I have unique access to climb, study, and manage tree habitat throughout our region, and I find it important to remind landowners that there is no published research at this time that supports the notion that removing deadwood improves the health of trees. Additionally, landowners can mitigate risks associated with all parts of a tree without removing it entirely, especially in low-risk areas.

Retaining deadwood can lead to healthier urban forests—but we can take it a step further. When opportunities arise, we can also enhance habitat value by creating “snags,” or wildlife trees, on residential properties. Not all snags are tall or dangerous, and I have safely created and monitored more than 400 wildlife trees used successfully each year as reproduction sites.

It is good practice as a landowner to be aware of wildlife protection laws, to leave habitat opportunities when possible, and to consider the best season for carrying out tree work. Remember that when it comes to trees, your decisions impact wildlife.

The author’s company, Arboriculture International LLC, started the Willamette Cavity Dweller Initiative to enhance local urban forests with tree material for cavity-dwelling species. Rather than remove trees to the ground, they safely retain and enhance valuable tree structure in which wildlife can live and reproduce. Learn more at www.arboriculture.international.

Having a snag as a habitat feature is one of many opportunities supported by the Backyard Habitat Certification Program, managed by Columbia Land Trust in collaboration with Portland Audubon. Learn more at: Backyardhabitats.org.

Illustration of a snag, a dying tree that offers habitat for cavity-dwelling wildlife. Art by Brian French