Land with Integrity

A New Tool Allows Our Land Stewards to Better Measure Ecosystem Health.

To the eye of an average hiker, the cold, rushing rapids at Columbia Land Trust’s Hood River Powerdale property are a sight to behold. Mount Hood stands tall in the distance over orchard lands, and birds sing as the sun peeks into the forests on the hillside. The setting is timeless in its beauty.

To the trained eye of an ecologist, the towering pine trees, native plant understory, and watershed tell a deeper story about the health and history of the landscape.

With field notebooks and reports in hand, Jen Zarnoch, Land Trust natural area manager, is joined by senior vegetation ecologist Joe Rocchio and vegetation ecologist Tynan Ramm-Granberg, both with the Washington Natural Heritage Program (WNHP). Together, they’re testing a new tool they hope will radically improve the Land Trust’s ability to answer some complex but critical questions: How healthy are the lands we steward? How effective are our restoration efforts at improving habitat? How should we prioritize our efforts moving forward?

The tool, dubbed the Ecological Integrity Assessment (EIA), is a standardized methodology for evaluating the health of a landscape’s ecology compared to its historic natural condition. Key ecological attributes help ecologists and land managers determine where a site lies on the continuum from functional and thriving to degraded and ailing.

The WNHP, housed within the Washington Department of Natural Resources, is charged with identifying the state’s rare species and rare and high-quality ecosystems. Rocchio and his colleagues spent the last decade evolving the EIA from a wetland assessment tool first developed by a network of natural heritage programs called NatureServe. They adapted the EIA so that a single set of criteria could be applied to every major ecosystem found in the Pacific Northwest.

“No matter the type or scale of the ecosystem,” Rocchio explains, “we’re primarily asking the same questions: which plant species are present, what is the structure of the ecosystem, what are the primary ecosystem functions of the area, and how well are they performing? Plant species are the primary focus of EIA measurements because they are closely tied to all other species and ecological processes, and because they are relatively easy and cost-effectivee.”

“This is a tool,” says Zarnoch, “that can help us look across all our lands in Washington and Oregon and determine how we’re doing.” Familiar with Rocchio’s work from her time with Washington Department of Natural Resources, Zarnoch sees the potential for the EIA to serve as a structured, science-based approach to land management for Columbia Land Trust. For the first time, the Land Trust’s natural area managers can use a single methodology to evaluate wetlands, upland forests, prairies, oak woodlands, riversides, sagebrush-steppe, and other habitat types represented across their 13,700-square-mile service area.

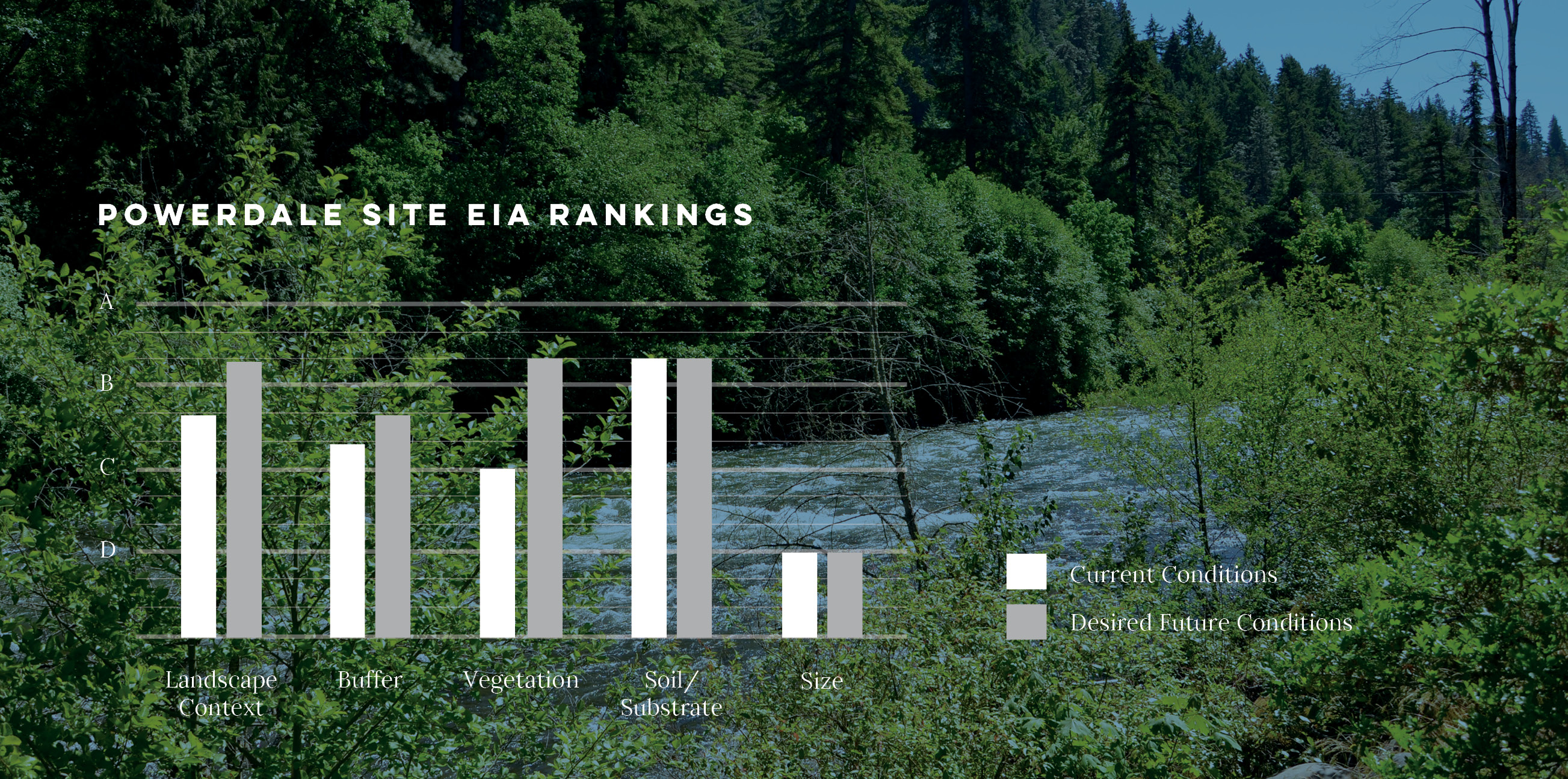

In addition to its versatility, the EIA allows land stewards to conduct assessments that are rigorous yet fairly rapid. By gauging characteristics of vegetation, hydrology, soils, and landscape context, a natural area manager can within a few hours assign an area one of four rankings: A (excellent), B (good), C (fair), or D (poor).

Plus, the EIA establishes shared protocols, allowing different land managers to formalize what traditionally have been more subjective views. The tool still requires requires professional judgment, including traditional ecological knowledge, but land managers can at least point to a specific attribute where opinions differ and learn from there.

After trials at sites like the one at Powerdale, Washington DNR and the Land Trust will continue to refine and calibrate the EIA. The Land Trust plans to conduct EIAs on each of its 95 stewardship units over the next couple of years to establish baseline conditions. Future EIAs will then allow stewardship staff to determine whether a site’s habitat condition is improving, stable, at risk, or declining. These determinations will feed into the Land Trust’s adaptive management process, tell us how our sites are doing, and help us prioritize our work accordingly.

Our stewardship team is optimistic that efficient monitoring, paired with EIAs, will result in better data, more time for restoration work, and a tighter feedback loop to get the most out of every dollar spent on managing and improving habitat. Ultimately, we’ll be able to move more land toward desired conditions for wildlife.

If the Land Trust’s early adoption of the EIA goes as planned, we are hopeful that the tool catches on with other land trusts. By creating a common language around ecological assessments, land trusts could provide a more complete picture of ecosystem health across the entire Northwest and beyond.